CSHR Participates In The IF Forum 2022 With a Keynote Speech On Human Rights In Sport

Authors -

David Grevemberg

Chief Innovation and Partnerships Officer David Grevemberg represented the Centre for Sport and Human Rights at the IF Forum 2022, a two-day event where International Sport Federations come together, that was celebrated this week in Lausanne.

With this year’s edition taking place under the theme of ‘Safe Sport and Sustainable Development’, Grevemberg participated in the opening session at the Olympic Museum with an inspiring and powerful keynote speech on Human Rights in Sport.

“Universal principles for good governance in sport provide a solid framework. However, human rights considerations can help to strengthen these principles even further”, he explained.

On day two, Grevemberg took part in the panel ‘Human Rights in practice - What we are expected to do?’ with Magali Martowicz, IOC’s Head of Human Rights; Alex McLin, Director of Gymnastics Ethics Foundation and Ashley Ehlert, Deputy General Secretary & Legal Director at the Ice Hockey International Federation.

Full text of the keynote speech is available below.

President Bach

President Ferriani

IOC Vice President Ser Miang

Madam State Councillor Brodard

Madam Vice Mayor Moeschler

Esteemed Friends and Colleagues

Ladies and Gentlemen

It is an honour to address you this evening. The subject I will cover is sport and human rights harnessing the potential of our social license. As many of us know, this is a topic of considerable importance in the public interest, prevalent in global media discourse, controversial in some contexts and widely celebrated in others. Is this just a place of high-risk stakes and overt challenges for international federations or somewhere that offers significant opportunities to deliver on the promise of sport?

The intent of my presentation isn’t to lecture or preach to you about why human rights are essential. After a brief scene-setter – I will first cover the architecture of the global sports ecosystem and how it applies to human-centric thinking; second, I will provide a quick overview of what’s at stake when we talk about human rights and how they are the foundation for not only showcasing our values but generating value; third, I will discuss how this directly impacts the work of international federations, and in closing – as VIPs in sport – I hope to leave you with a point of reflection for an esprit de corps on how we approach this critical area of our work and the benefits such a social licence can bring.

Twenty-two years ago in Monaco, the famous South African President, Nelson Mandela (affectionally known as Madiba), told us “how sport had the power to change the world”. A decade before, in 1990, on a visit to the United States Congress in Washington DC, just four months after his release from serving a 27 years prison sentence during the Apartheid regime, Madiba said: “to deny people their human rights was to challenge their very humanity”.

At the turn of the millennium and for the next two decades, with Madiba’s inspiration for embracing our common humanity – sport took the challenge. Leading the charge, the Olympic Movement inspired us with a call to action, “Celebrate Humanity”. Seven years later, we began championing “The Best of Us” by promoting stories of human triumph and individual achievement on and off the field of play.

Approximately eight years later, we were challenged with yet another call to action stressing the importance of unity and a common belief that “Together we can change the world”.

And four years later, in 2020, sport and humanity faced the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic – a challenge that could only be overcome collectively because we were, and are, “Stronger Together”.

These inspirational campaigns reflected hope in humanity through the power of sport. To deliver on these messages of hope, we take responsibility for a social license to respect, protect and promote human rights.

Within this last decade – the expectations of various actors across the global sports ecosystem to respect human rights and core labour standards have become more sophisticated, louder, and more targeted. They hold international federations and sports events to a higher account for their impact (either negative or positive) on people, their communities, the environment, and the prosperity of economies hosting events. This is because of the distinct influence of sport. In 2022 alone, we see more than ever that human rights are being discussed globally. Why? Because of sport.

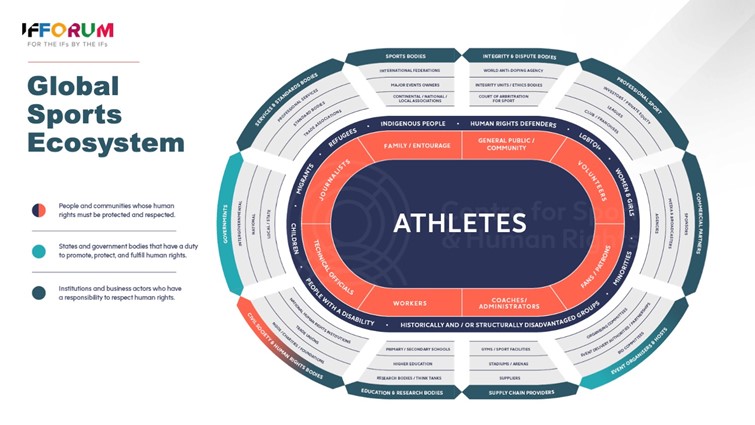

So let’s look at the world of sport through its impact on people. To do this, we must take a human-centric view of our global sports ecosystem.

This diagram, designed by the Centre for Sport and Human Rights, was our first attempt to map the interconnectivity and interdependencies of this ecosystem. At its centre are people, starting with the athletes – and including other roles, we perform throughout our lives in sport. On the periphery of the field of play is a list of diverse characteristics and vulnerabilities that may require special considerations or adaptations when creating safe and welcoming sports environments for everyone. The seating blocks represent different institutional actor groups, with seating rows representing sub-actor groups, with every institution influencing our ecosystem having a seat in the arena. Every individual and institution has specific roles and responsibilities, given who they are. Through their interactions, the impact is created – which is either harmful or beneficial to others.

As in an arena during a competition – all of us operate under a social license in this ecosystem – reflected through our behaviours, decisions, and actions. All these can have a butterfly effect across our industry, which can have detrimental or beneficial consequences on our reputations, finances, operations and success; for instance, we can be regarded as an industry that is inclusionary or exclusionary, integrated or segregated, safe or reckless, or ultimately responsible or irresponsible for the people we serve and support.

So for sports bodies to truly fulfil their roles responsibly – it must be understood what is at stake for the people impacted by their activity – starting with fundamental human rights.

Some of the various human rights and labour standards impacted in and through sport are showcased on this slide. Over the past few years, municipal, national and regional governments and intergovernmental bodies worldwide have begun to adopt legislation and establish guidance on respecting human rights. Such measures include setting new standards in due diligence, funding requirements and expectations on robust audit and reporting mechanisms that will profoundly impact day-to-day sport and event hosting. Some laws have been reformed, and there are more explicit expectations on acceptable behaviour and conduct, many now aligned to normative international human rights and labour standards.

However, every context is different, and therefore we must consider these diverse levels of development as we do our business. For instance, in 2021, the Council of Europe revised the European Sports Charter to include under Article 6 Human Rights provisions. This closely aligns with new, more robust human rights due diligence regulations coming into effect across many Western European countries in 2025. Bodies like UNESCO, OECD, OIF, ASEAN, CARICOM, the African Union, the Commonwealth, and many others have started to adopt human rights-related declarations and set guidelines, all impacting the conduct of sport. Many have made these moves to protect the safety of children and vulnerable groups and/or make progress on the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Much of this can be daunting or overwhelming for some national, continental, and international sports bodies – the concepts, accessible language to sport, standards, expectations, and guidance can be challenging to wrap our heads around on a good day, much less understand the nuances to apply them effectively and consistently, especially across diverse contexts.

But there is an entire field emerging that organisations like the Centre for Sport and Human Rights and others are developing to support all actors across the sports ecosystem in demystifying and structuring this material through easier-to-understand and applicable frameworks, policy templates, research initiatives, education modules, advisory support and much more that is written in a language that will resonate with sport.

Rachel Davis, Vice President of Shift, who will address you tomorrow, will provide more information on the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights – which are essentially the definitive guidelines on how businesses, including sports bodies, should, at a minimum, approach and act on the topic of human rights across their workstreams.

Questions like – Why do we need to do this? What’s the value? What do we gain? Are we not opening ourselves up to more risk? Where do I start? How do I avoid getting too involved or political? These standard questions are expected in any emerging field with such high stakes.

However, the reality is – once we learn more about human rights – and understand what we are responsible for, what we are already doing well, and where we need to improve. The question that typically follows is, “how can we NOT afford to do this?” It’s a process that is part of a continuous journey of engagement, learning, application and refinement.

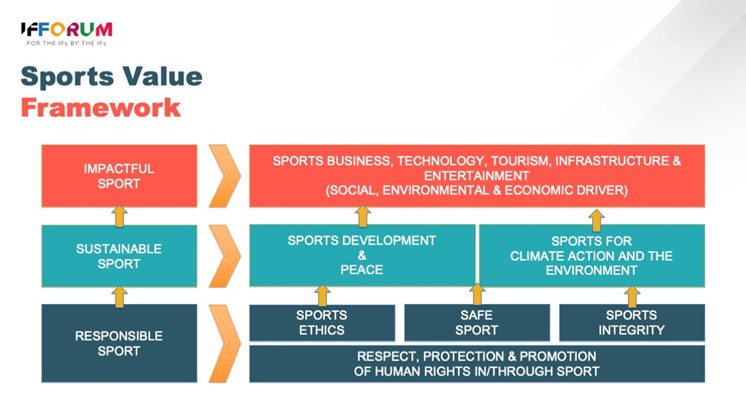

We often hear about sport and human rights concerning abuses, violations, oppressions and crimes – which have direct links to sports ethics, safe sport and sports integrity and, of course, which must be taken seriously and responsively addressed and remedied with care and effectiveness for all concerned. But we should also note that many human rights achievements have been championed and attained in and through sports. These elements showcase our will and ability to effectively manage risk and create positive change that ultimately delivers what we call “Responsible Sport”.

This diagram displays a framework for how we can attain maximum value from the social license that sport gives us. If our ultimate goals are to ensure the prosperity of the business of sport while impacting the world positively – or, in other words, creating Impactful Sport – then we must be widely trusted, uphold legitimate standards, and be deemed credible. If we subscribe to this, we must work up from the foundation – which is Responsible Sport. The bedrock upon which Responsible Sport is built is the respect, protection and promotion of human rights and core labour standards. In this approach, we set out the principles, standards and thresholds by which sport ethics, safe sport and sport integrity measures can be effectively implemented and monitored. This robust human-centric design establishes the foundation upon which the structure of Sustainable Development can be built. Ultimately, Responsible Sport and Sustainable Sport provide the architecture that Impactful Sport uses to thrive universally.

This diagram displays a framework for how we can attain maximum value from the social license that sport gives us. If our ultimate goals are to ensure the prosperity of the business of sport while impacting the world positively – or, in other words, creating Impactful Sport – then we must be widely trusted, uphold legitimate standards, and be deemed credible. If we subscribe to this, we must work up from the foundation – which is Responsible Sport. The bedrock upon which Responsible Sport is built is the respect, protection and promotion of human rights and core labour standards. In this approach, we set out the principles, standards and thresholds by which sport ethics, safe sport and sport integrity measures can be effectively implemented and monitored. This robust human-centric design establishes the foundation upon which the structure of Sustainable Development can be built. Ultimately, Responsible Sport and Sustainable Sport provide the architecture that Impactful Sport uses to thrive universally.

The levels of development and familiarity with specific human rights issues vary by context - culturally, geographically, historically, religiously, and politically, to name a few. Applying this framework is another example of how human-centric systems can help us identify pathways to manage risks better, identify gaps, create causal linkages and discover more efficient and effective ways of generating value in and through sport that is responsible, sustainable and impactful.

So how do human rights apply practically to the work of IFs?

Here we have what is largely recognised as the six workstreams that most commonly encompass the work of IFs.

Here we have what is largely recognised as the six workstreams that most commonly encompass the work of IFs.

Starting with governance – having clearly outlined commitments, statutes, strategies, policies, and institutional positions on human rights is becoming a standard expectation across many sectors and a prerequisite for good governance. The universal principles for good governance in sport provides a solid framework. However, human rights considerations can help to strengthen these principles further.

In the management workstream (how we run the daily business of an IF), many jurisdictions where IFs are headquartered already require respect for human rights and core labour standards through various legal systems and employment laws (impacting areas like staff health, safety, and well-being); Areas like diversity, equity and inclusion; grievance and remedy, procurement policies and supply chain due diligence, are areas within many IFs where more progress can be made. Another area under this workstream that requires particular emphasis is how we implement human rights considerations in our risk management processes.

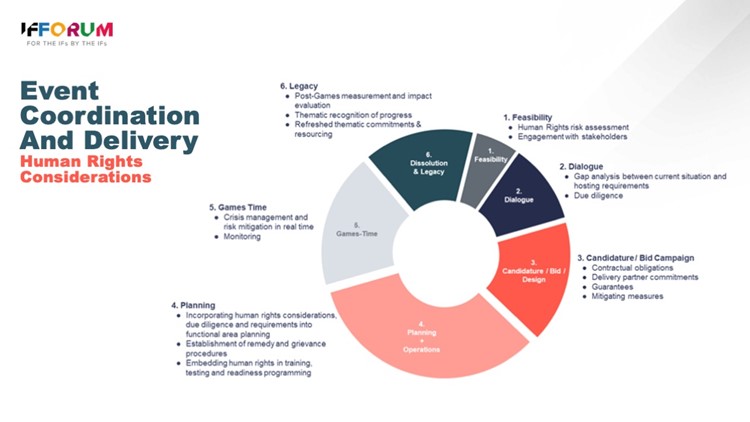

In the event coordination and delivery workstream, how we assess, negotiate, award, plan, and deliver events which respect human rights and leave a positive social legacy in their wake, requires specific steps to be taken throughout the event lifecycle. There is often a misconception that embracing human rights will limit our ability to host events in certain places. As the Centre’s Sporting Chance Principle 10 states – “Bidding to Host Sports Events Should be Open to All”. Ultimately it’s about a process that incorporates internationally recognised Human Rights Standards and enables engagement with prospective hosts whereby gaps between international standards and local laws and practices are identified, and measures to address such risks are proposed. This framework for engagement, risk identification and collaboration is where the real opportunity for social legacies lies. Ultimately, this is about running responsible events that, at a minimum, do not harm and realise their full potential to make the world a better place.

Development and Education activities are critical for developing knowledge, enhancing competencies and building capacity to ensure human rights are respected on and off the field of play by athletes, team officials, technical officials, administrators and others. The design of practical tools that helps us better respect and protect one another’s human rights brings our values to life and forges a sustainable working culture. Many IFs are already implementing robust safeguarding training systems, which is an element of this work. However, there are many other areas, and much work remains.

For Communications and Marketing – It starts with using the correct language and sincere and genuine narratives we can wholeheartedly standby through our actions. Taking a human-centric approach and upholding human rights standards helps us to do this. But equally important is how we inclusively engage with stakeholders in a two-way conversation through our platforms to build trust and legitimacy in our work.

And finally, revenue generation – who do we want to partner with and why – how do they align with our values, what impact will we create together, and what is the meaningful purpose of our relationship? These are all questions that both IFs and their commercial partners (specifically sponsors, broadcasters and private equity investors) ask themselves and one another. Incorporating many of the points discussed throughout this presentation into consideration during the deal-making process has become a critical factor in these relationships that can ultimately build trust, legitimacy and credibility together.

So hopefully, this starts to give you a sense that human rights considerations are everywhere, whether we realise it or not– it’s already part of our daily business. The good news is that many tools are available to effectively get started and manage these considerations while harnessing untapped potential.

For example, this diagram created by the Centre for Sport and Human Rights provides an overview of a sports event lifecycle and the human rights-related considerations that should be taken at each phase. We have developed and are continuing to build resources and support to help sports bodies create human rights policy commitments, manage bidding and event delivery systems and support across many other areas.

So in closing, I hope this has provoked some interest and curiosity in sports and human rights. And has also given you more confidence in unpacking a subject that can seem daunting. I’m looking forward to tomorrow’s panel discussion on the topic with Ashley, Magali and Alex, which promises to be informative and engaging – and will highlight some of the great work already being done in this area.

As promised, I said I would leave you with a point of reflection. Each of us in this room is a VIP in sport.

In harnessing this social licence afforded to us by sport and human rights, - What if we were to look at what it means to be a VIP just a bit differently? What if instead of just standing for the very important people we are – that VIP stood for what we stand for - being values-based, impact-driven and purpose-led? Now more than ever - bringing new meaning to our work in sport is critical. By taking this approach, I believe we can harness our social licence and deliver together for better – by first building trust; then by achieving new standards that legitimise our work and our impact; and over time, with trust and legitimacy on our side – our credibility will continue to rise.

Thank you for your attention and the opportunity to speak with you this evening.

📸 SportAccord - Robert Hradil